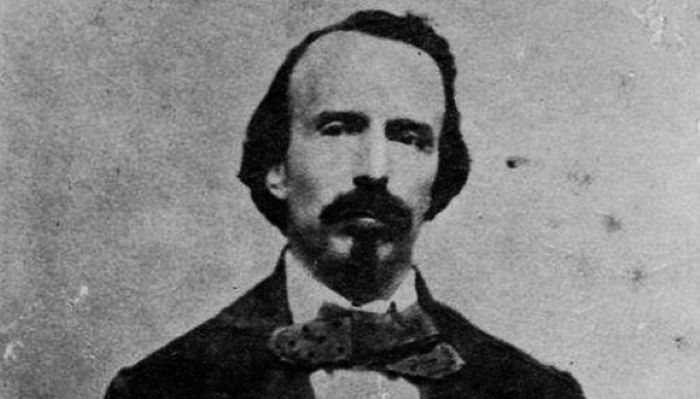

La Demajagua in October 1868 was an old sugar mill with just over ten caballerías of sugarcane and a recently purchased 30-horsepower English steam engine, two trains, a still, and a batey (a small village with a larger and more comfortable hut than the others), the Bayamo lawyer and landowner Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, standing out. This hut was the scene of the events. The farm is located on the edge of the Gulf of Guacanayabo, a splendid landscape of natural beauty that can still be seen today.

Two days earlier, it had already become the headquarters of Céspedes and the Manzanillo rebels who supported him. From the house, emissaries left the day before for Caridad de Maraca, in Vicana, southwest of Mexico, to convey the order of the uprising. Pedro de Céspedes, the younger brother of the clan, commanded there. The rendezvous was in the Naguas mountain range, in the foothills of the Sierra Maestra.

The hustle and bustle grew more intense from the 9th. Several groups of involved parties arrived and camped on the batey. They were led by chiefs from the Manzanillo region: the Izaguirres, the Zuásteguis, the Masós, the Calvars, and other men close to Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. According to eyewitnesses, there were approximately two hundred men.

The decisions had been made days before (contrary to the position of some eastern leaders of the conspiracy, who were still reluctant to rise up on the 10th). On the night of October 9, only the final touches of the patriotic declaration were made. Céspedes ordered the sugar mill’s slave crew to play their Afro-Cuban songs and, inside his house, kneeling before the Virgin of Charity, he vowed to fight to the death to achieve Cuban independence. If we add to these two highly symbolic gestures—the songs of cultural and ethnic fusion and the Catholic prayer—the important fact that the main conspirators and their leader were Freemasons, as well as Céspedes’s liberal-radical ideology, we have, in a single bundle, a set of symbols that provide much information for properly interpreting the origins of our independence effort. Historiography still has much to investigate regarding these indicators.

In the early hours of dawn on October 10, the leaders Bartolomé Masó, Juan Hall, and two hundred mounted men entered La Demajagua, thus completing the first encampment of Free Cuba. After the final deliberations among the leaders of the uprising, the ringing of the sugar mill bells summoned the conspirators to the batey esplanade. It was around ten in the morning. Céspedes, leader of the revolt that in a few hours would transform into a powerful abolitionist and republican revolution, addressed those present. There, in a magnificent scene of integration of Cuban nationality, Blacks and whites, slaves and landowners, small rural landowners and freedmen, united to create the first day of the homeland. A previously unknown flag was unveiled, and the Declaration of Independence was sworn, the document that argued the rebels’ case to the world and urged them to join the fray.

Immediately afterward, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes addressed his slaves specifically, declaring them absolutely free and inviting them to become soldiers for another freedom more important than simple individual liberty: that of the homeland he had born there. They were beginning to cease being slaves and become men who would, a little later, mingle their blood with that of their former masters. It was a gesture for all time, and to underscore it and give it historical force, the proclamation of abolition was made from the position of armed insurrection, that is, in open and deadly confrontation against the colonial power. The other slave owners followed suit.

Those men were not fully aware that they were participating in the most sublime act in the history of their people. Perhaps they knew they were making a reckless decision and that the battle they were undertaking would be arduous and bloody. They sought the freedom of the Cuban people, of Cuba as a nation. Seen from the distance of time, it was a morning filled with light, the light of the Caribbean and, on the other hand, the light of history.

The rest of the day was spent continuing military preparations and receiving information on the progress of the Spanish authorities in Manzanillo, where Céspedes had recruited two officers, one from the Spanish army and one from the police. When the firearms at their disposal were counted, the patriots realized they only had thirty-six rifles; the rest were bladed weapons and pointed wooden spears. The machete, used for agricultural work, was evidently the most common weapon of that motley Liberation Army.

In the early hours of October 11, in the pitch black of night, the embryonic contingent of that fledgling army set out, determined and quixotic, toward the town of Yara and into history.

Cuba was never the same after October 10, 1868. The revolution sparked by the most radical liberals in the far east of the country marked a break in the historical course of the Spanish colony with its antiquated system of plantations and slavery.

It was an insurrection that cost thousands of lives and destroyed half the country, but it sowed in that sea of blood the seeds of independence and the aspiration for a sovereign republic. The only corner of Latin America where the Bolivarian impulse had not yet reached was beginning to be shaken by the movement of the Cespedista revolution, pro-independence, patriotic, and abolitionist.

[ TAKEN FROM CUBA DEBATE ]