Imperialism and Revolution

Program #12

The insights and historic errors of the Revolution of 1968 in the USA

November 6, 2019

By Charles McKelvey

The spectacular ascent of the United States from 1776 to 1968 was based on conquest, colonialism, slavery, and imperialism, fundamentally contradicting the proclamation of the nation as a democratic republic founded on liberty and justice for all. There was thus a historic contradiction between, on the one hand, the undemocratic base of U.S. economic development; and on the other hand, the proclaimed democratic values of the nation. The contradiction was resolved through various ideological maneuvers: racist concepts, formulated with supposedly scientific support, that justified conquest and slavery; an omission of global and regional economic relations, obscuring the economic advantages that the nation obtained from colonialism and slavery; and in the twentieth century, a Cold War ideology that downplayed the nationalist character of the worldwide anti-colonial revolutions, stressing their socialist dimensions in order to portray them as part of an international communist conspiracy against democracy.

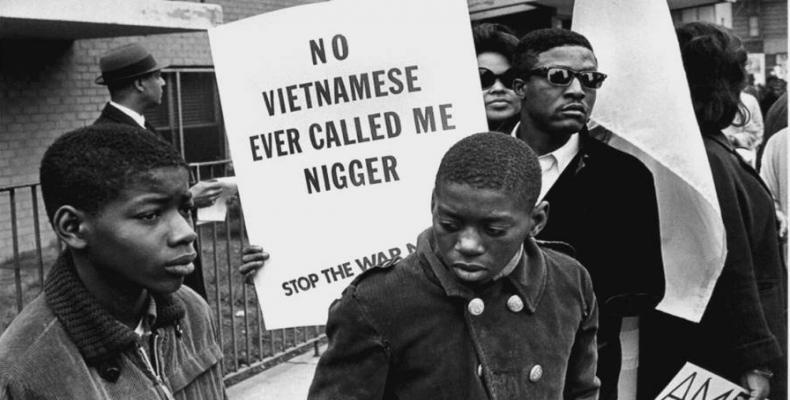

These ideological maneuvers were not only lies; more than that, they constituted false premises that shaped public debate, making impossible an understanding of national and global dynamics. There were two nationalist movements, however, that threatened to unmask the false premises of U.S. public discourse, namely, the African-American movement and the Vietnamese nationalist struggle. The political impact of these movements created the possibility of freeing the people from ideological distortions and empowering them to change the direction of nation, placing it more in accordance with democratic values.

The African-American movement emerged in response to the denial of fundamental rights to U.S. citizens of African descent, including legally sanctioned and mandated discrimination and segregation in the U.S. South. The movement had originated in the urban North during World War I, and it expanded to the urban South in the 1950s, on the basis of the expansion and increasing strength of black churches, colleges and protest institutions in the urban South in the post-World War II era. From the outset, the movement was committed to the protection of the citizenship rights of all, regardless of race, and including social and economic as well as political and civil rights; and it called for foreign policies that respected the sovereign equality of all nations, including the nations of Africa, Asia and Latin America. In the period 1955 to 1965, the movement gave strategic emphasis to civil and political rights in the South. Beginning in 1966, the movement turned to demands for black control of black institutions, in response to the failure of white allies of the period 1955-65 to support further reforms following the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965; and it renewed its call for an anti-imperialist foreign policy, in reaction to the Vietnam War.

The Vietnamese Revolution was led by Ho Chi Minh. A nationalist who encountered socialism in Paris in 1919 and who studied in the Soviet Union, Ho forged a creative practical synthesis of Marxism-Leninism and Vietnamese nationalism. From 1930 to 1945, he led the Indochinese Communist Party and the Vietminh Front (League for the Independence of Vietnam) to the taking of effective political control, and he declared the Declaration of Independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam on September 2, 1945. The French war of reconquest culminated in a 1954 peace accord among the Western powers, which divided Vietnam into two temporary zones, one under the authority of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the North, and the other under the control of a French puppet government in the South. The United States became increasingly involved in the conflict, and recognizing that Ho would win proposed elections to unify the temporary zones, it encouraged the establishment of South Vietnam as a permanent state; which in turned prompted the formation in 1960 of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, in order to coordinate emerging popular resistance to the puppet government, which included the development of local structures of popular power.

The Cold War ideology prevented U.S. policymakers from understanding the conflict in Vietnam, as is clear from the reflections on the war that Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara wrote years later. With Cold War blinders, the Kennedy Administration could not see that the South Vietnamese government was a puppet government installed by France and the United States to preserve a colonial presence in the face of the nationalist aspirations of a people who had become politically conscience and united. Not understanding this reality, they mistakenly believed that South Vietnam, with U.S. support, could establish itself as a viable and stable nation. By 1964, it had become clear that the South Vietnamese government was politically unstable and did not have control of its territory. U.S. policymakers erroneously concluded that the cause was insufficient U.S. support, which was signaling a lack of commitment to the government of South Vietnam. They therefore increased U.S. military presence from 23,000 military advisers at the end of 1964, to 180,000 troops by the end of 1965 and 280,000 by the end of 1966, and reaching 550,000 by 1968. But based on erroneous assumptions, the escalation of the war did not result in the attainment of U.S. objectives in South Vietnam, and at the same time, U.S. casualties mounted, reaching 100,000 (including dead and wounded) by April 1967.

During the period 1965 to 1970, there emerged widespread opposition to the war in the United States, with white middle class students in the vanguard. The student/anti-war movement had emerged as a student movement in the early 1960s, and it evolved to become an anti-war movement in the late 1960s, as the U.S. war against Vietnam escalated. The movement was fueled by the contradiction between, on the one hand, U.S. pretensions to democracy, and on the other hand, and the denial of rights of black citizens and the unleashing of the colonialist war in Indochina. This contradiction was increasingly evident to white middle-class students, who had internalized the democratic narrative of the nation, as a result of the upward mobility experienced by their families, many of which were part of the great European migrations to the United States of the period 1865 to 1925.

The popular revolution of the period 1966 to 1972, including the civil rights/black power and the student/anti-war movements, had all the elements necessary for a successful popular and democratic revolution. The key ideas were formulated: the need for the people to take power from the elite; the obligation of a democratic society to protect the political, civil, social and economic rights of all citizens; a coalition among the various popular sectors on the basis of common interests; and the obligation of the nation to respect the sovereignty and equality of all nations, standing in opposition to imperialism and the neocolonial structures of the world-system. But such key ideas were expressed as part of a confused mix, which included critical strategic errors that limited the possibilities for the movement to gain greater support among the people. These errors included the adoption of techniques of sabotage in a political culture that had not come to accept such a strategy of resistance, the use of extreme slogans offensive to many of the people, the display of countercultural manifestations that were alien to the sentiments of many of the people, and the application of dogmatic Marxist concepts that had no relation to the actual reality. The charismatic leader who would have been capable of putting together the key pieces and unifying the movement toward the necessary road, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in 1968. Subsequently, the black power movement was silenced by systematic oppression in the period 1970 to 1972, and the student/anti-war movement dissipated as the war wound down and the compulsory military draft for young men was eliminated.

Since that revolutionary moment of the late 1960s, the productive decline of the United States has the consequence that its global dominance today is confined to financial capitalism and military technology. It lacks the political will to reduce these sectors and channel funds toward investment toward sustainable forms of production, and without such political will, its decline is irreversible. At the same time, the neocolonial world-system has encountered the obstacle of the sustained revolutionary resistance of the colonized, who have refused to accept the fate assigned to them by the neocolonial world-system, of which the heroic Vietnamese nationalist struggle and Cuban resistance to the six-decade U.S, blockade are important and symbolic illustrations. Moreover, the world-system, which historically expanded by conquering new lands and peoples, has reached the geographical limits of the earth and has overextended it ecological limits. Under these political and economic conditions, there is no possibility for the United States to restore its economic, political, financial, and ideological hegemony. Trump wants to make America great again, but the followers of Trump have an anachronistic goal, disconnected from real economic conditions and possibilities. Meanwhile, the moderate and progressive sectors of the political establishment do not understand the necessary structural transformations of the world-system nor the necessary adjustments in U.S. direction.

The necessary road in the United States must be led by a genuinely progressive current of thought and politics, which does not yet exist as a unified politically viable alternative, as a result of the demise of the Revolution of 1968, which not only lost at the historic moment, but also was unable to sustain itself is an alternative current of thought and practice. Any progressive alternative, if it is to be realistic and have economic and political viability, must be based on understanding of the structures of the neocolonial world-system, an understanding that requires appreciation of the insights of the anti-colonial revolutions of the Third World. Accordingly, we are going to turn in this program to the insight of the popular revolutions of the world, beginning with the case of the Cuban Revolution, which we will begin to explore next week.

This is Charles McKelvey, speaking from Cuba, the heart and soul of a global socialist revolution that struggles for a world more just, democratic, and sustainable.