GJ: Hi GJ here with JJ and welcome to this special edition of the Arts Roundup.

JJ: Yes, glad that you could join us.

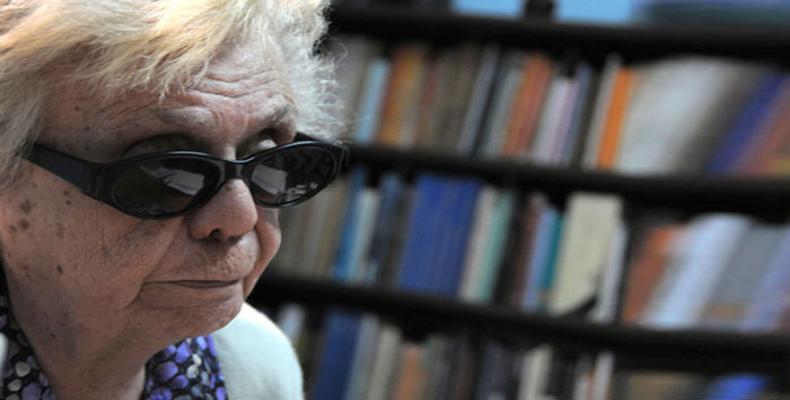

GJ: On the heels of Cuban Culture day, Cuban author and essayist Graziela Pogolotti published an erudite article in the last edition of Juventud Rebelde entitled How Cuban Culture Came To Be and we are pleased to bring you this English translation today.

JJ: Harassed by poverty and tuberculosis, poet José María Heredia died in exile. Poets Placido and Juan Clemente Zenea were shot. Cuban Apostle José Martí fell in Dos Ríos. While these poets forged images for a nation still non-existent, the intellectuals, on the other hand, developed an ideology through teaching. They broke the sclerotic dogmatic tradition imposed by the colony. The priest Félix Varela had a chair at the Seminary of San Carlos and San Ambrosio. It was not students he had, he formed disciples. Inevitably, the path he outlined would lead to politics and open debate in the Cortes in Spain . Persecuted, Father Varela found refuge in emigration without return. He did not stop thinking about Cuba and exercising a spiritual teaching. More prudent and no less effective, José de La Luz y Caballero gave himself up to education. In the classrooms, the fighters-to-be were maturing. Since then, ethics and politics began to intertwine in an inseparable way, a vision that would reach with José Martí its most intense projection in incendiary prose and in the concrete conjunction of theory and practice.

GJ: At first, the ideas circulated in the preserves of the enlightened minorities. The dramatic circumstances of a colonial and slave society favored the development of converging concerns in sectors of the silenced majorities. The metropolitan power perceived the latent threat. To contain the danger, they applied extreme violence against José Antonio Aponte and the repression of the so-called Conspiracion de la Escalera. Politically, socially and culturally, and turned into a popular cause, the idea of nation became full blown during the Ten Years' War of 1868 to 1878.

In feverish days, without sleep, struggling to avoid the probable intervention of the nascent empire, José Martí combined action and preaching. The unity between the veterans of yesterday and the new generation, between the representatives of the different layers of society and attenuate the survivals of the old localisms, had to be consolidated. The notion of independence integrated the vindication of an ideal of justice. The homeland was becoming the conjunction of "root and wing" with the creative impulse of dreams always pursued. He did not have a classroom, but they called him Master.

JJ: Graziella Pogolotti writes in How Cuban Culture Came To Be: Republican frustration had an overwhelming initial impact with signs of skepticism, opportunism and corruption. The apparent lethargy did not last for long. The planting had not been useless. In the 20s of the last century, the impact of reality, influenced by a structural crisis of the dependent economy and the subordination of governments to the dictates of the empire, induced the intellectuals to leave their chambers, to gain visibility and participation in the public life. That commitment did not subtract them from surrender to personal fulfillment that also helped to build the nation. It was necessary to go deep into the roots and conform the wing from the perspective of contemporaneity.

Julio Antonio Mella founded the José Martí Popular University. The historians proposed the rereading of our becoming. Fernando Ortiz revealed the preterm areas of our cultural miscegenation. Amadeo Roldán and Alejandro García Caturla, with the active complicity of Alejo Carpentier, posed the challenge of incorporating the rhythms of African origin into the art of symphonic composition. The poets sharpened their ears in a similar direction. José Zacarias Tallet and Emilio Ballagas did it. The scores reached their crystallization with Nicolás Guillén's Motivos de son. The painters traveled to Paris in search of learning the trade and contemporary languages. With that experience, they forged a visual imaginary that, according to many critics, marks the true birth of our plastic arts. By multiple paths, root and wing converged again.

GJ: In the context of the neocolonial Republic, the initiators of the 20s and the generations that succeeded them did their work from extreme precariousness. When they could, they earned their livelihood by performing other trades. Dramatic example, the murder of Judge Alejandro García Caturla cut off the life, in full maturity, to one of our most brilliant composers.

Art education suffered from incurable anemia. Faced with so much helplessness, the Cuban Revolution took up some founding ideas and focused its attention on the promotion of culture. From the literacy campaign to the university reform, education constitutes the backbone of a democratizing purpose that underpins national sovereignty for the benefit of the fullness of the person and in favor of the conversion of science into a productive force. The institutional system that begins with the foundation of the Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos or ICAIC lays the foundations for the professionalization of the artists, for the production of the work and for the formation of numerous critical spectators and at the same time, for the rescue and protection of the national patrimony. The art education system incorporates the most valuable creators into teaching, and offers unprecedented possibilities to potential talents. The construction of the National Arts Schools of Cubanacán aspires to favor the dialogue between the different artistic manifestations.

JJ: After the commemorative days of the day of Cuban culture, it is advisable to give quiet time to meditation on the challenges of the hour with the participation of the youngest. The irruption of new technologies, the presence of the market in certain areas of creation help to model mentalities and aspirations. Paradoxically, the proliferation of areas of research in universities and centers dedicated to the social sciences has not translated into a productive exchange of knowledge of such significance in the reduced intellectual circles of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Open to the world, remiss to narrow localism, Cuban intellectuals were, in adverse circumstances, root and wing, observers of reality and creators of the imaginary. We must eliminate barriers, stereotypes and spent formulas. It is up to the institutions to favor the circulation of thought. In a time dominated by the expansion of frivolity and the cult of the ephemeral parade of celebrities, thinking is a way of doing.

GJ: And thank you for your company on this special edition of The Arts Roundup in which we presented a recent essay by Graziela Pogolotti How Cuban Culture Came To Be. I’m GJ

JJ: And I’m JJ. Until next time.