Hi, Gerwin Jones here, and welcome to The Real Story, with Lena Valverde and Juan Jacomino. Neoliberal parties, the corporate media, a conservative judiciary, oil lobbyists, the white elite and right-wing groups, with generous help from outside, have ganged up to derail the Brazilian government. And it’s all being made to look like a popular uprising against a corrupt regime

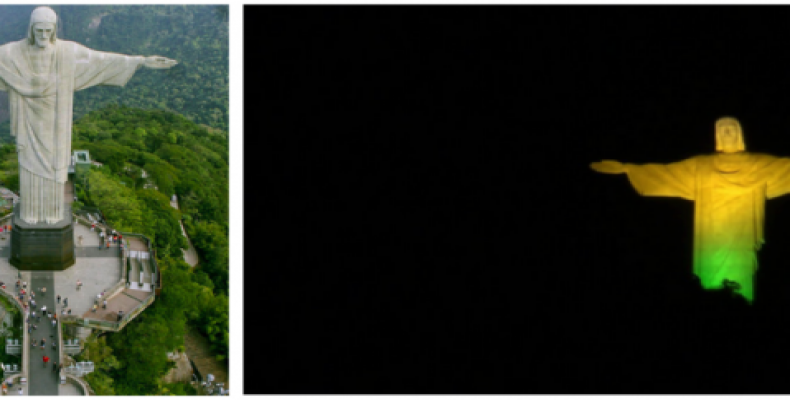

JJ: In November 2009, The Economist put Brazil on its cover. Brazil Takes Off, read the headline, emblazoned on a photo of Rio’s iconic statue of Christ the Redeemer rising above blue waters like an inter-stellar rocket. Predicting that “Brazil is likely to become the world’s fifth-largest economy, overtaking Britain and France,” the magazine said that South America’s largest economy should “pick up more speed over the next few years as big new deep-sea oilfields come on stream, and as Asian countries still hunger for food and minerals from Brazil’s vast and bountiful land.”

LV: Indeed, In 2009, even as the world was reeling from a catastrophic financial crisis, The Economist saw Brazil as the great hope of global capitalism. Back then under Lula da Silva’s leadership, the country was witnessing unprecedented prosperity and social change.

GJ: Lula’s personal rise from shoe-shine boy and motor mechanic to the presidency of the biggest Latin American country was the stuff of legends. He was the subject of several books and a Brazilian box-office hit. At the G-20 summit in London in April 2009, US president Barrack Obama called him the “most popular politician on earth.”

JJ: The Brazil story began to lose some of its shine in 2013, especially in the eyes of international business media. In September 2013, The Economist put Brazil on its cover once again. The report was scathing and blasted Rousseff, who had been running the country for three years by then and was facing an election the next year, for doing “too little to reform its government in the boom years.”

That had not been a good year for Brazil. The economy was faltering and hundreds of thousands of people had come out on the streets just ahead of the FIFA Confederations Cup to protest against corruption and demand better public services. The economy appeared to have stalled entirely.

LV: Seven years later, Brazil is looking like a completely different country. Lula, who retired in 2010 with an 80% approval rating, was detained this month for questioning in a multi-billion dollar corruption scandal that has seen some of his Workers Party (PT) comrades go to jail. His successor, President Dilma Rousseff is facing impeachment in the Congress.

The country’s economy shrank by 3.5% last year, and this year won’t be any better. Inflation is in double digits and hundreds of thousands are facing unemployment. No one cares two hoots about the Rio Olympics, which are less than five months away. And the corporate media – global and local – has already written off Lula, Rousseff and Brazil.

GJ: So what went wrong between 2009 and 2013? How did Rousseff, declared the most powerful woman in the world in 2010 by Forbes, suddenly become weak and allegedly incompetent? How did the Brazil story turn from one of hope to that of despair in such a short time?

JJ: The answer is simple – oil, and the money, power and politics it generates. In 2007, Brazil discovered an oil field with huge reserves below the ocean surface, exceeding 50 billion barrels – the largest in South America. Brazil was now the new darling of the world’s oil merchants, and Wall Street.

State-owned Petrobras had enjoyed a monopoly over oil exploration in Brazil since its creation in 1953, but the sector had been opened up to Royal Dutch Shell in 1997. In 2007, Lula partially restored Petrobras’s monopoly over Brazilian oil. Laws made under the guidance of Rousseff, who was Lula’s chief of staff, gave the company sole operating rights, with all its earnings going to government’s social programs on education and health.

LV: Let’s not forget that the US State Department and Energy Information Agency (EIA) soon began lobbying Brazilian officials on behalf of American companies. In secret US diplomatic cables released by Wikileaks in 2010, it was revealed that the Americans were worried about the presence of state-owned Chinese companies in Brazil, with one cable detailing how the US was trying to get the country’s laws changed to its advantage.

Soon, Chinese firm Sinopec became active in oil exploration in Brazilian waters as it agreed with the law that stipulated a minimum 30% stake for Petrobras in all ventures. It was the end of the West’s honeymoon with Brazil. “As their lobbying failed to win oil contracts, Brazil became a villain, like Venezuela.

GJ: But surely the government also made a mistake by placing too much hope in Petrobras and oil, forgetting that it’s a commodity whose price can go down?

JJ: Coming to power on the promise of making Brazil a more equal society with a strong welfare state, oil and Petrobras were at the core of the government’s plans to use public resources and money to fight poverty, create public jobs and bring development to remote areas in Brazil. Petrobras was not a bad bet. In 2007, the company’s market capitalization was $190 billion. In 2010, Lula’s last year in power, Brazil had grown at 7.5 % and things were looking up. Although there was a drop in Petrobras’ capitalization and profits in the coming years, it remained one of the biggest oil companies in the world.

But things were set to get worse.

LV: Enter the NSA In June 2013, Edward Snowden, a US National Security Agency (NSA) system administrator, escaped to Hong Kong with a trove of top-secret documents. Snowden released a series of files that showed how the US government was spying on politicians, governments, companies and social movements across the globe. Brazil was one of the top targets of the NSA. The Americans claimed their surveillance was part of their counter-terrorism measures, but the documents on Brazil – and countries like India – revealed an entirely different picture. It was soon evident that the NSA’s main targets in Brazil were Petrobras and Rousseff.

Rouseff’s email, official telephone and personal mobile phone had been tracked by the NSA, as had every email, phone call, message and all official documents on Petrobras’s network. With its trade secrets and information about its assets downloaded in NSA facilities, Petrobras was now a sitting duck. Its fall had just begun.

JJ: In March 2014, Alberto Yousseff, a convicted money-launderer who had been arrested five times, began to sing like a canary after negotiating a plea-deal with prosecutors in Curitiba, the capital of the southern Brazilian state of Parana. He named many big leaguers whom he said had benefitted from bribery, kickbacks and money-laundering in Petrobras. Since then, the probe into this scandal, being led by Judge Sergio Moro, has singed the country’s top businessmen, oil executives and, most importantly, the leadership of Dilma’s party.

LV: Last month, the unthinkable happened. The most popular leader in the history of the country was on the verge of being arrested for alleged corruption related to Petrobras. On March 3, the federal police picked up Lula from his house under a “coercive warrant” (which forces a person to testify in a case) and grilled him for five hours at their office in Sao Paulo’s domestic airport.

As Lula was detained and released, tension gripped the country with a section of Brazilian society – upper crust and mostly white – celebrating the police action, while the other part protested against the “coup”. Brazil was vertically divided on the day Lula was detained.

GJ: And at this drastic moment I have to say ‘To be continued…’ and thank Lena Valverde and Juan Jacomino for their contribution to The Real Story. For RHC I’ve been your host Gerwin Jones. Until next time, Ciau

Program The Real Story April 7

Related Articles

Commentaries

MAKE A COMMENT

All fields requiredMore Views

- Venezuela's attorney general denounces Salvadoran president as the top leader of the Maras

- Washington sanctions UN expert Francesca Albanese for documenting Israeli genocidal aggression against Gaza

- Cuba reiterates commitment to social protection policies

- Israel admits Iranian missiles damaged Netanyahu's Tel Aviv office

- UN expert affirms Israeli torture of Palestinian prisoners is widespread and systematic